Immaculata News

Dr. King’s Legacy: 50 Years of Progress

Tags:

On the evening of April 4, 1968, as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. stood on a balcony of his hotel room in Memphis, Tenn., an assassin took the shot that ended his life. He was in Memphis to support striking sanitation workers.

Although King is mostly regarded for his civil rights work in the South, he devoted extensive time to raising awareness about racial injustices in the Northeast including supporting the thousands who protested the exclusion of African-Americans from Girard College in Northeast Philadelphia.

“President Johnson’s Civil Rights Act of 1964 led to the end of official legal discrimination throughout the U.S., but King’s assassination in 1968 demonstrated that racism was still a prevalent force,” states William Watson, Ph.D., professor of history at Immaculata.

According to Watson, Chester County, where Immaculata University is located, has often been thought of primarily as a place where the Underground Railroad operated in Antebellum years in the nineteenth century. However, like the rest of America, it has been a complicated place to describe in terms of race relations. In 1830 there were still five African-American slaves residing within the county and in 1911 Zachariah Walker was lynched by a white mob in Coatesville. However, a new generation was making its mark when West Chester native and civil rights activist Bayard Rustin helped organize King’s 1963 March on Washington.

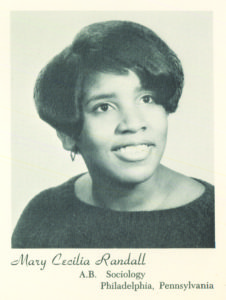

As with any national tragedy, the death of King resonated in the hearts and minds of Immaculata’s students including members of the class of 1968, which graduated two African-American students. The campus community at Immaculata felt the turbulence and unrest of the era. “I know we all railed against the injustices of racial segregation and certainly supported Dr. Martin Luther King’s message,” states Gail Poinsett Froggatt ’68. Although not many Immaculata students were marching in the streets, Froggatt recalls that she and her classmates spent a fair amount of time in their dorm rooms singing songs that reflected the tone of the times, such as the civil rights anthem We Shall Overcome and Bob Dylan’s Blowing in the Wind. Even today, songs with the same familiar sentiment are composed and passionately performed, but take on a new tone—from artists like Swizz Beatz and Scarface’s protest song, Sad News, and R&B singer Lauryn Hill’s Black Rage.

“The day Dr. King died, I felt an immense sadness, as if I had lost a member of my family,” states Mary Randall ’68, an African-American sociology and education major. “I felt alone, but not lonely.”

In July, before Sally Tamburello Winterton ’68 entered her freshman year, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. She remembers during her years at Immaculata that many students took a bus into Philadelphia to hear King speak. She notes that it was a lovely, crisp April day on campus when she learned of King’s death from classmates.

“The day Dr. King died, I felt an immense sadness, as if I had lost a member of my family,” states Mary Randall ’68, an African-American sociology and education major. “I felt alone, but not lonely.” Randall’s friend, who had a TV in her dorm room, allowed Randall to watch the news by herself. “Although there were not many blacks at Immaculata when I went there, everyone was so gracious and paid special attention to what my needs were,” Randall states of the day King was killed.

That afternoon students gathered in the chapel to acknowledge the day’s tragic events. Although Randall did not attend the gathering, she remembers that her friend, Yvonne Duglas, the other African-American student from the class of 1968, spoke to those who assembled. After graduating from Immaculata, Randall became more active in the protest movement while serving as a teacher and administrator in the Philadelphia School District for 35 years. When Randall was growing up, she notes that the textbooks never depicted African-Americans. To raise the self-esteem of the black students whom she taught, she brought in any books that she could nd that included images of African-Americans. “The need for self-esteem was great in the black community at the time,” she adds.

Through various events, AACS chose to focus on the impact of AIDS in the black community. Pictured are members of AACS volunteering at the annual AIDS walk in Philadelphia.

In the 50 years since King’s death, the country has made strides regarding race relations. However, the recent years have been filled with news stories that indicate the country may still be divided in its beliefs and ideals of true equality.

Currently, according to the U.S. Census, 6.3 percent of the population of Chester County identifies as African-American. Immaculata continues to diversify with 14 percent of the undergraduate population identifying as African-American/Black in 2016, which is slightly above the total U.S. population of 13 percent identifying as such.

As president of the African-American Cultural Society (AACS) at Immaculata University, Tanaya Reed ’19 is doing her part to continue advancing social equality by sharing her heritage with the campus. AACS presents special events during Black History Month, engages in volunteer activities, and holds open discussions on pertinent topics such as HIV/AIDS in the black community, the African diaspora across the world and how black men can take the lead. Last semester, the club held a hip-hop dance night.

While spending six weeks student-teaching in Peru, Reed encountered racist remarks from a tourist while eating breakfast one morning. At that moment, she felt King’s presence when she needed it most.

Sister Cathy Nally, IHM, executive director of mission and ministry at Immaculata, attends a presentation with the African-American Cultural Society president Tanaya Reed ’19 and moderator Joseph Healey, Ph.L., associate professor of philosophy.

“I felt all this anger bubble up inside me, and I was ready to lash out,” Reed states. “But I really did hear a voice say, ‘Stop, what about Martin Luther King and all those people who paved the way for you? They had hot coffee thrown in their faces, [were] spit at and called names.’ If they can do it, so can I,” Reed comments exultantly.

“The lessons of King live on!” says Kalus Queh ’20, who serves as social chair for the AACS. She notes the unparalleled esteem that King holds in American history.

“He played a big role in history, and he gives us hope as a country,” she adds.

May Amisial ’20 agrees. “He paved the way for black people today.” She references previous generations of African-American women who were not able to vote or attend college. She is grateful for people like Mary Randall who also paved the way at Immaculata.

However, there is one thing these young students still ponder: how could King be so humble amidst all the prejudice? Perhaps this was his greatest strength.

Masanue Outland believes that the country has come a long way—but not far enough.

“Just because we had a black president doesn’t mean everything is fine.” Outland says that people who are not African-American do not understand the challenges and how hard it can be. According to recent studies by the National Partnership for Women, black women are paid just 49 to 69 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men. The average gap in Pennsylvania is 68 cents for every dollar.

Despite the obvious disparity in pay and other inequalities, these students are determined to carry forth King’s legacy. “If Dr. King could live by the Golden Rule, then we can too,” states Reed.

“I come here from the front lines of the civil rights movement in the South to tell you, ‘You are somebody.’ Let us have a sense of somebodiness. Don’t let anybody make you think that you are not somebody.”

—Martin Luther King, Jr.,

“Freedom Now” Rally in Philadelphia, August 1965

“The day Dr. King died, I felt an immense sadness, as if I had lost a member of my family,” states Mary Randall ’68, an African-American sociology and education major. “I felt alone, but not lonely.”

“The day Dr. King died, I felt an immense sadness, as if I had lost a member of my family,” states Mary Randall ’68, an African-American sociology and education major. “I felt alone, but not lonely.”